Polly Tootal

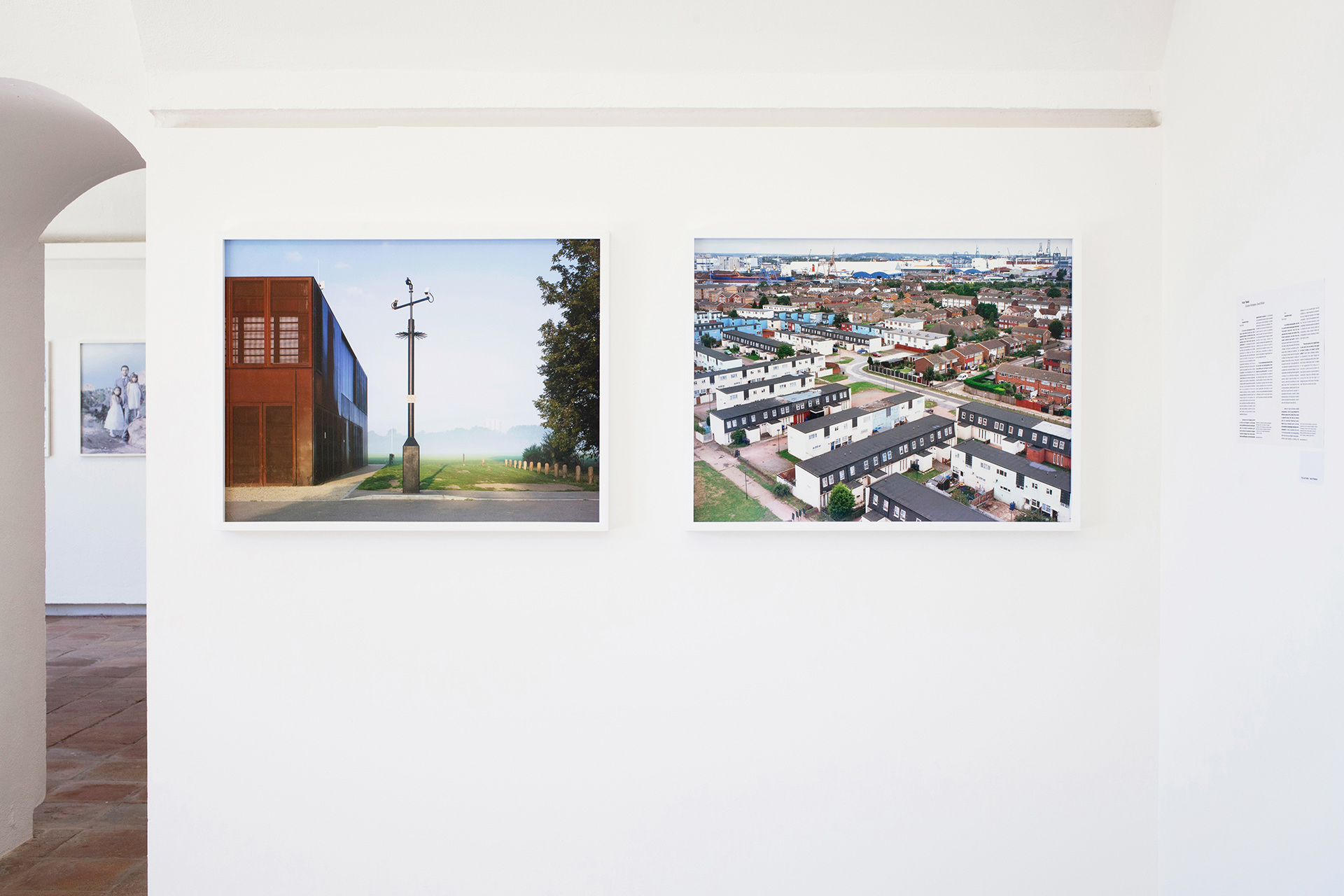

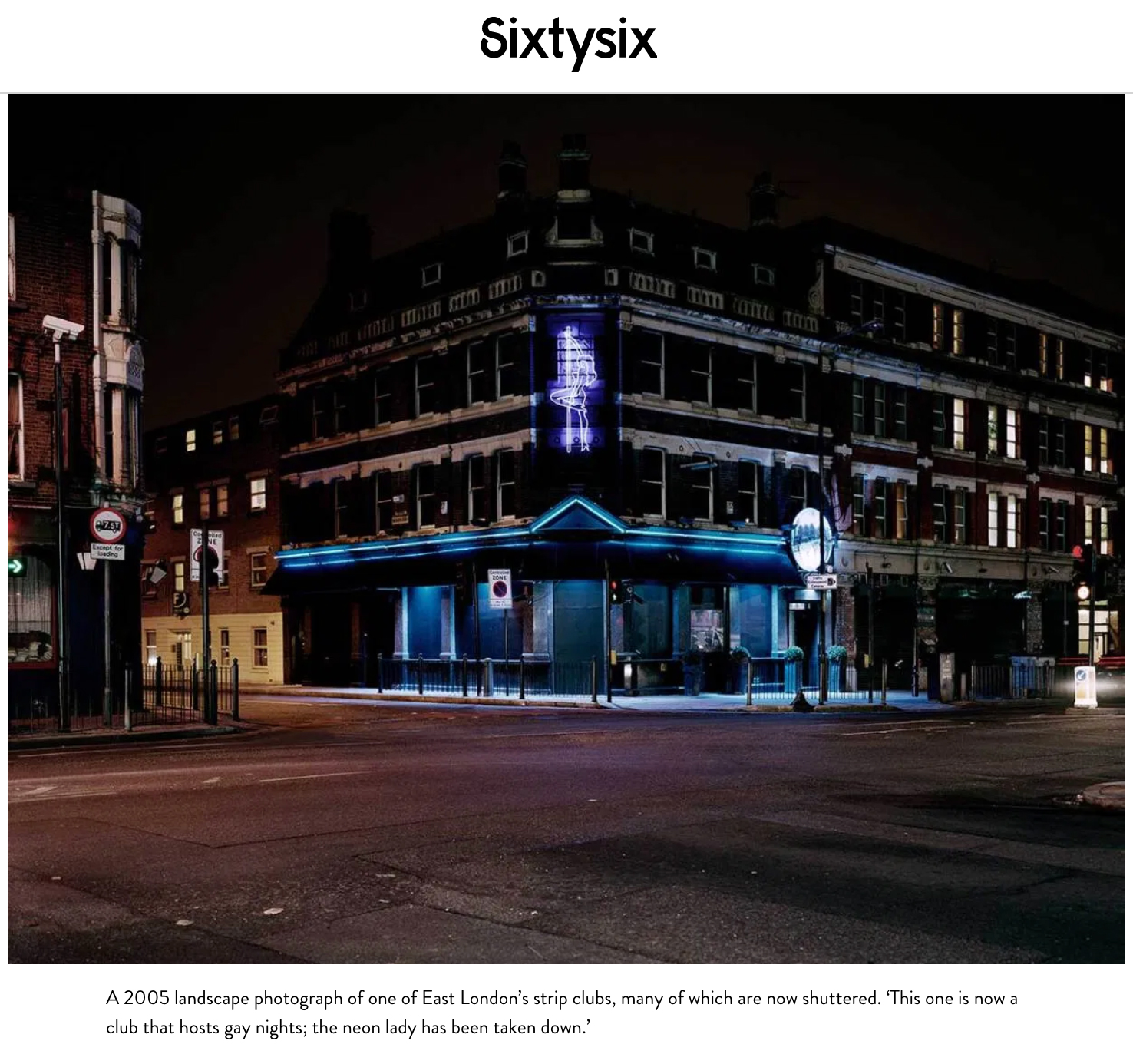

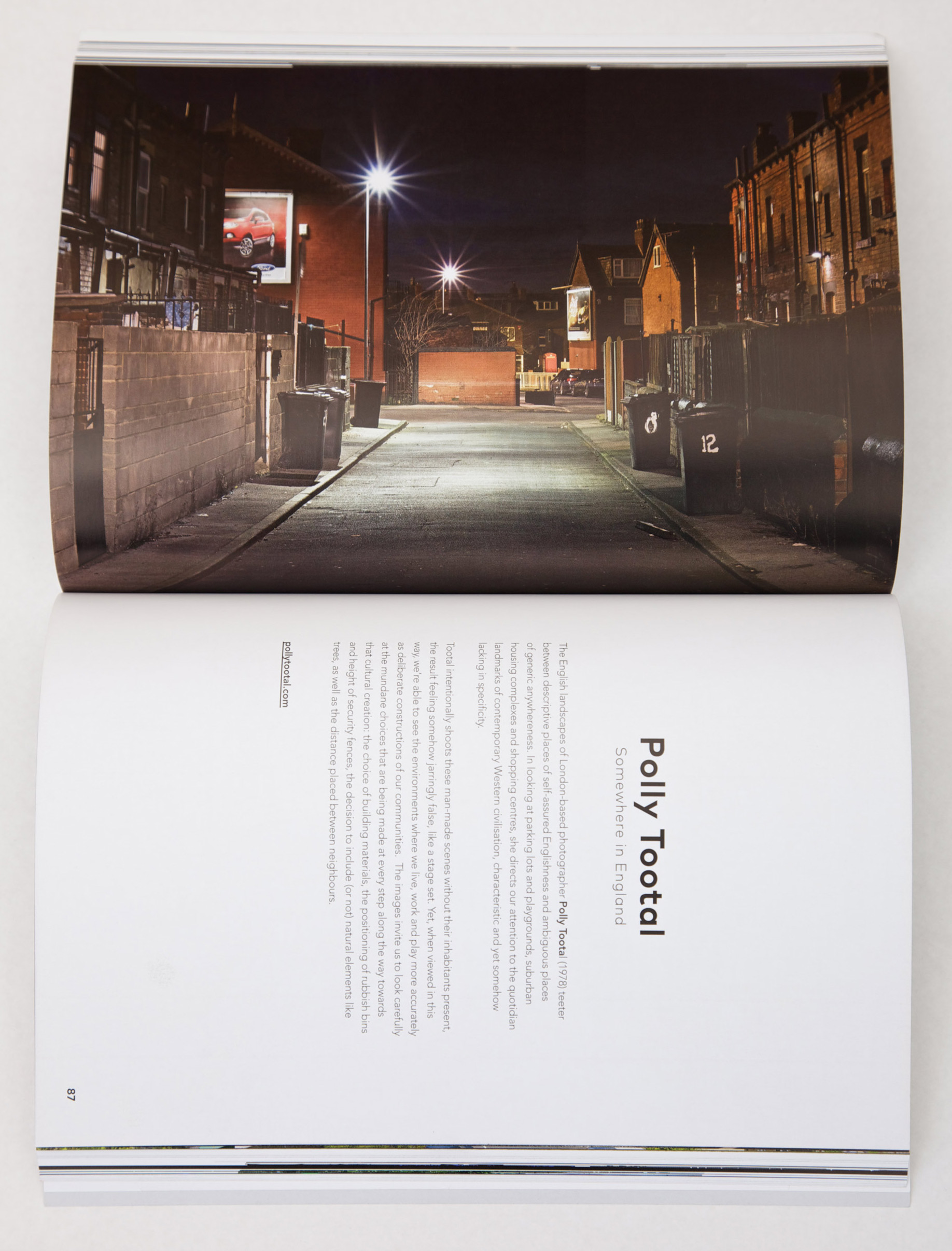

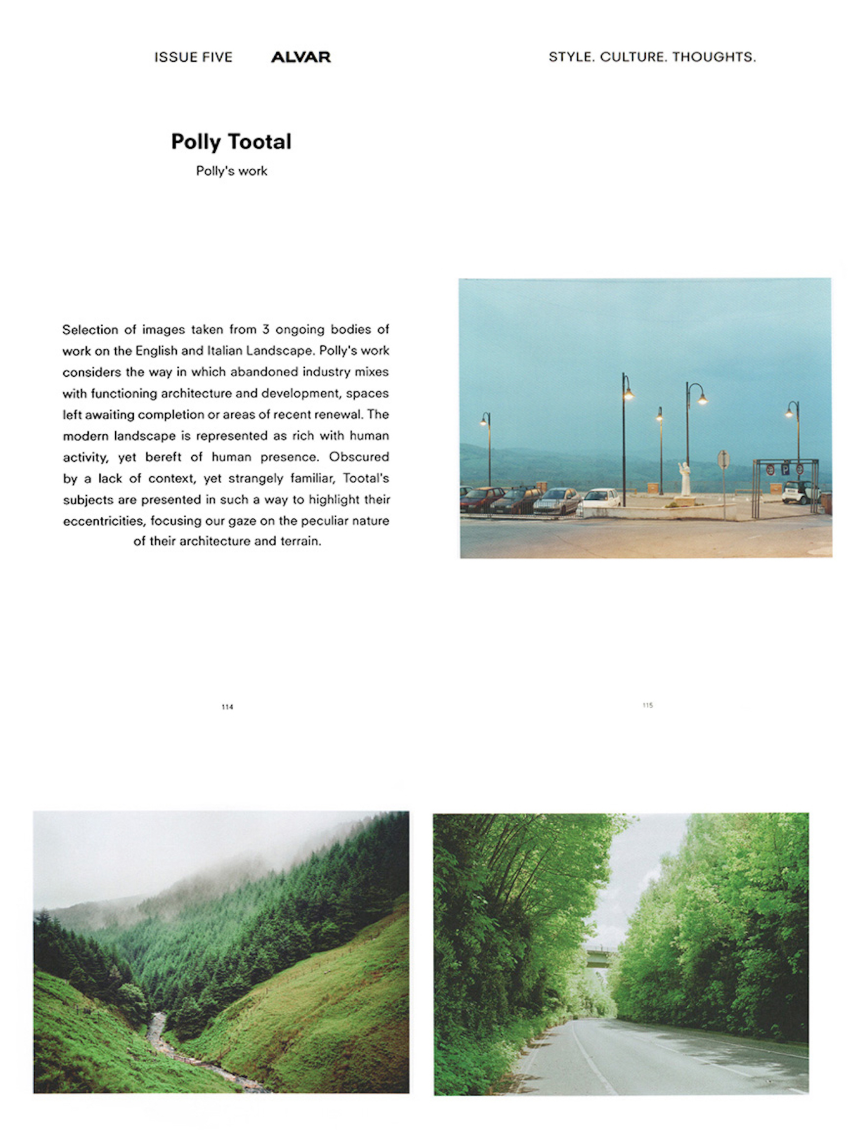

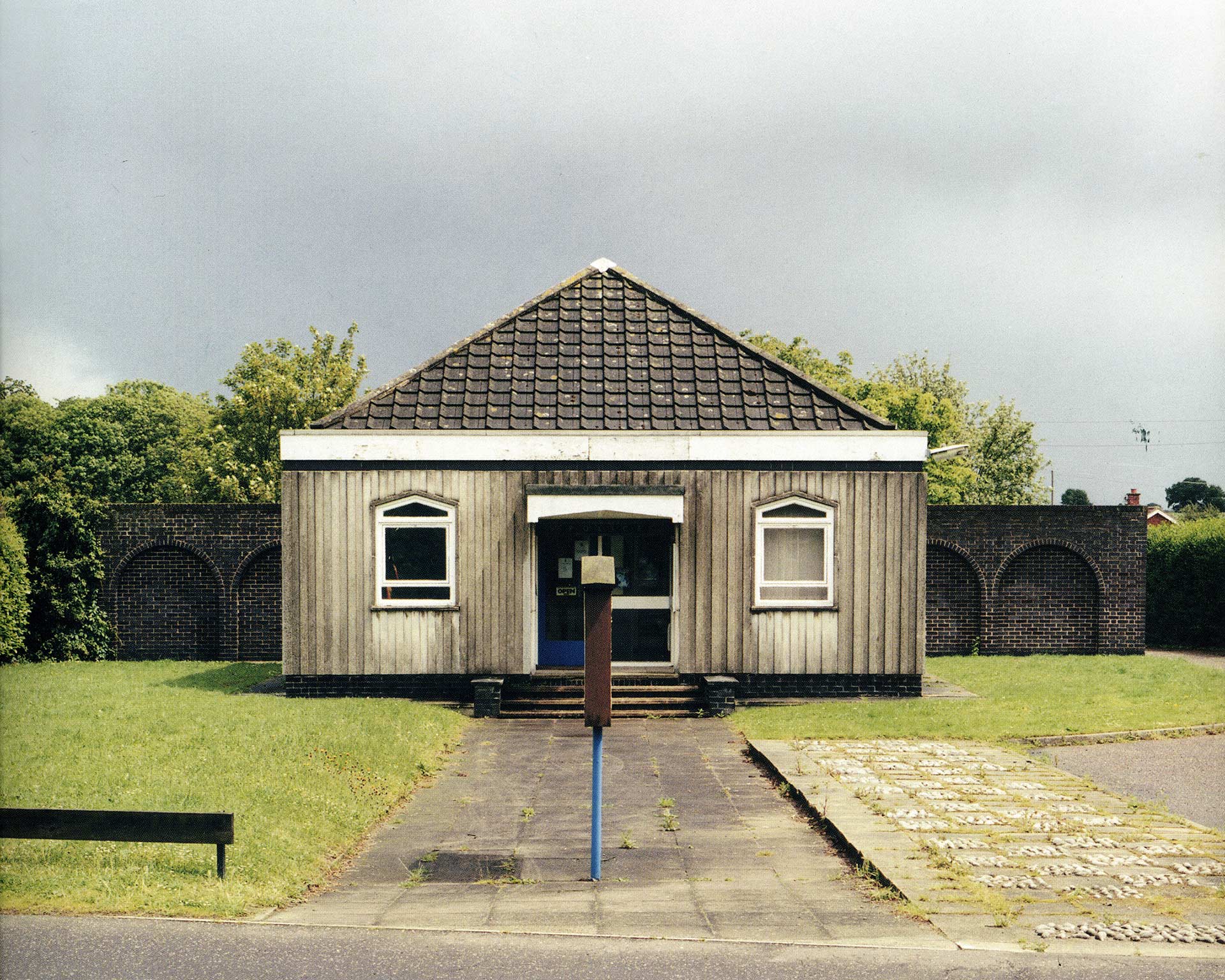

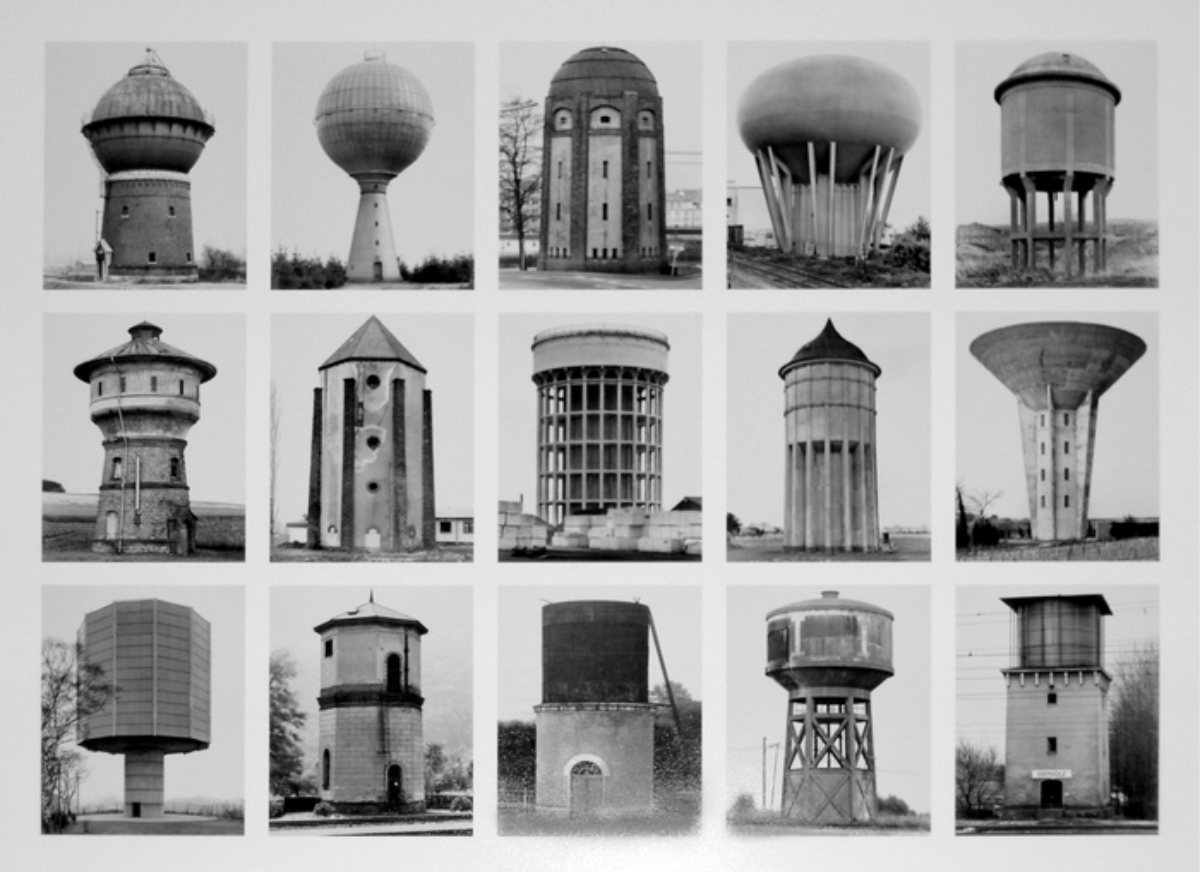

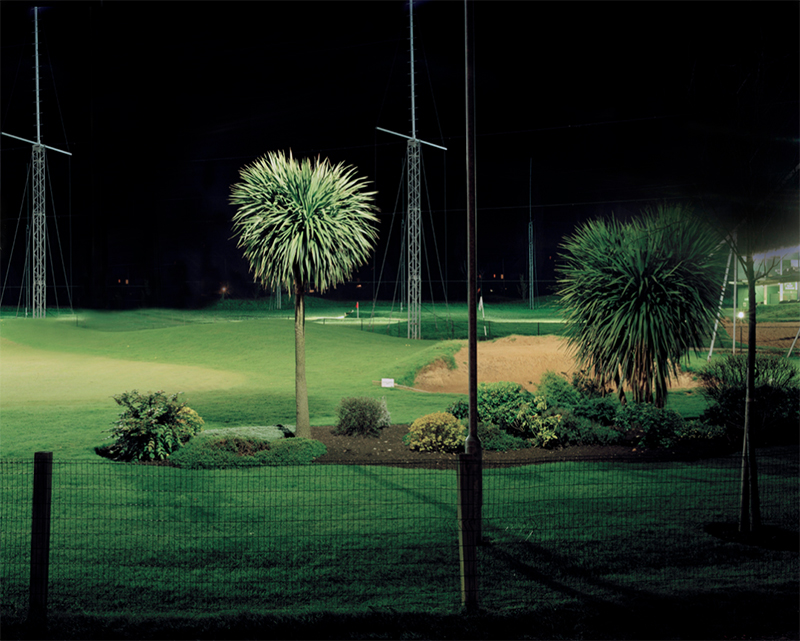

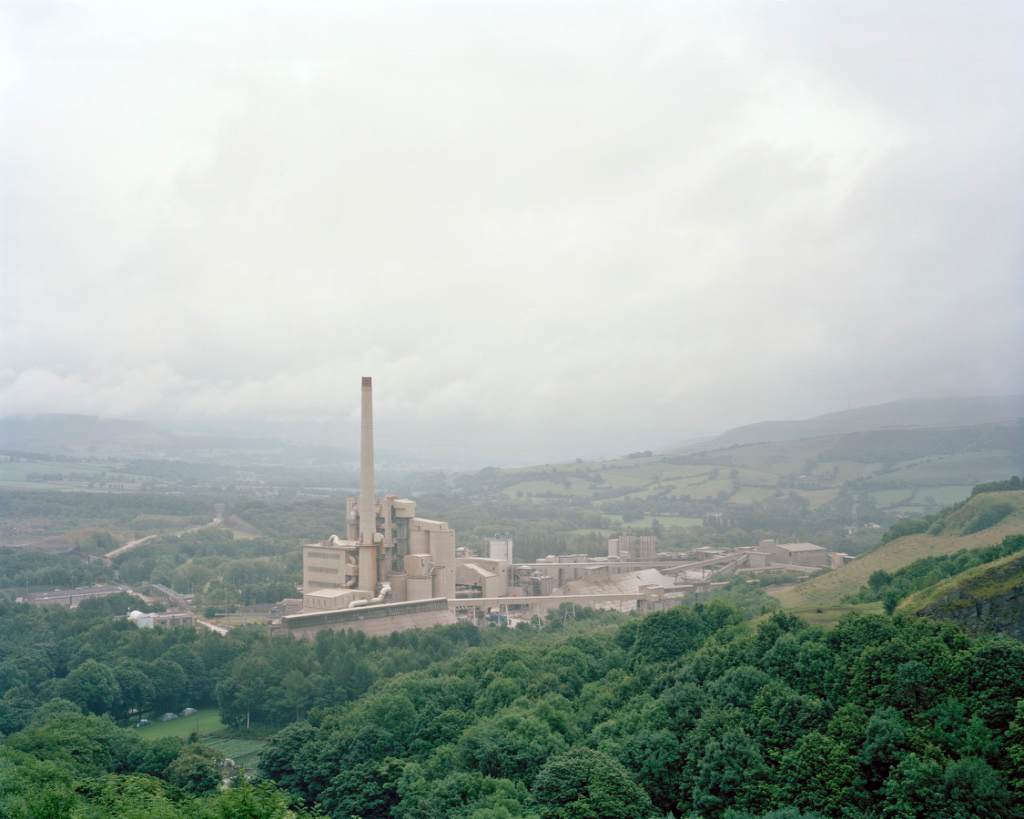

Tootal’s photography has emerged out of a continual exploration of the possibilities of space between a variety of extremes; theatre/reality, the contemporary world mirroring history, transience/permanence, the bizarre in the banal. Tootal’s ongoing topographic project Somewhere In England began in 2010 and is an exploration of undisclosed, anonymous landscapes in the U.K. Shooting mainly at dawn or twilight, these public places devoid of people appear otherworldly. Within the images she attempts to present a cultural critique on contemporary social issues whilst highlighting the idiosyncrasies of public space and illuminating the nondescript landscape in these large-scale works. Concerned with how contemporary geopolitics restrict and displace different societal groups due to poverty and injustice - her work focuses on liminal zones, the outskirts of cities where urban and infrastructure meet, highlighting the chaos and control that power forces upon populations and the environment.

Polly Tootal has lived and worked in London since graduating from Editorial Photography at the University of Brighton. Her landscape studies have been awarded the Prix Du Public Vile D’Heres Photographie 2015 and The Association of Photographers Award – Landscape Series 2010. She has been commissioned to depict the connections between people and place for clients such as Airbnb, Ink Global, and Air France, and fashion and lifestyle brands LVMH, Monocle Magazine and Madame Figaro magazine. Tootal presents regularly in solo exhibitions, group shows, and at art fairs throughout Britain, Europe, and North America. Notably, she exhibited at the Palazzo Rialto as part of the Venice Architecture Biennale 2014. Prints of her work are held in private collections in the USA, Europe, and the UK.

'Polly brings a sense of mystery and wonder into all areas of her work. Her graphic compositions emphasise the almighty industrialisation of our world, while her quiet portraits remind us of our delicate and vulnerable humanity. This interesting dichotomy is a welcome new visual voice in the industry.' Gem Fletcher.

ARTICLES

Vostok Magazine - Climate Crisis Issue - https://www.instagram.com/p/Cz2p9tgJhb-/

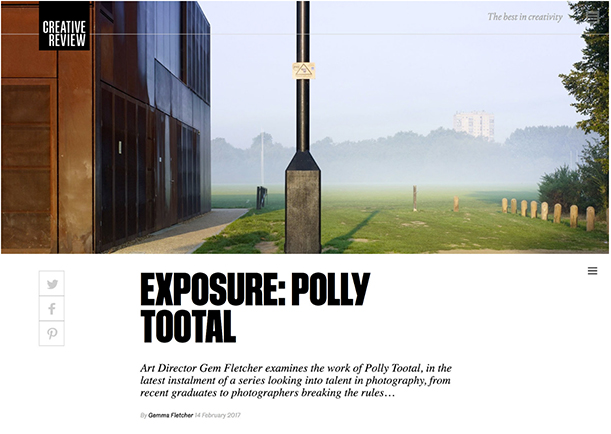

https://www.creativereview.co.uk/exposure-polly-tootal/

https://www.life-framer.com/polly-tootal/

https://phmuseum.com/ptootal/story/the-hands-that-built-this-city-5be6914efd

https://fotoroom.co/the-hands-that-built-this-city-polly-tootal/

https://fotoroom.co/somewhere-in-england-polly-tootal/

https://www.life-framer.com/urban-life-favorite-shot/

https://sixtysixmag.com/polly-tootal/

https://www.artsy.net/article/editorial-the-everyday-england-of-polly-tootals-photographs

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/in-pictures-53279397

https://www.life-framer.com/street-life-2020/#iLightbox[gallery-1]/18

https://www.life-framer.com/urban-stories-2019/#iLightbox[gallery-1]/12

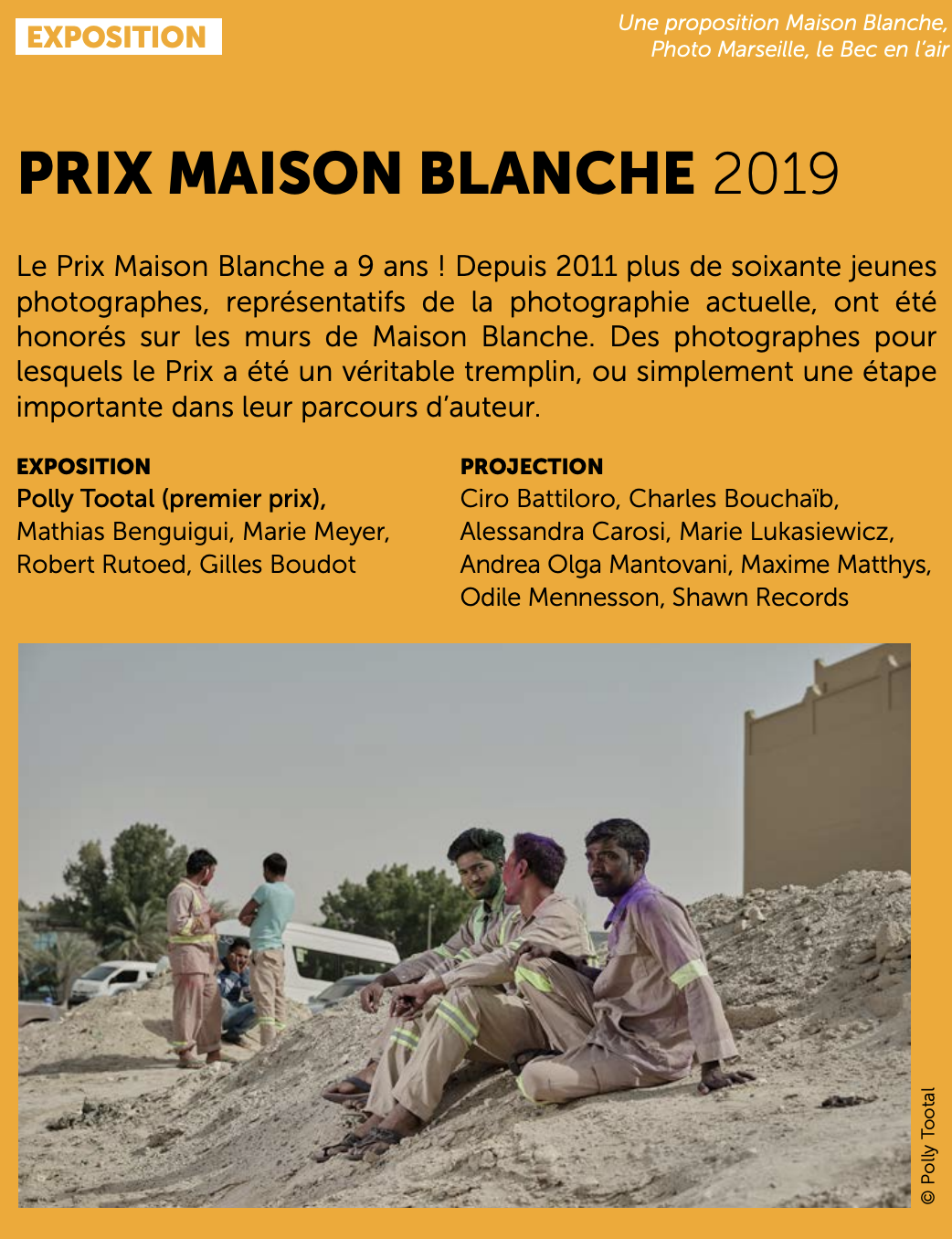

Awards 2023 - PhMuseum Womens Photography Grant - 3rd Prize Recipient2019 - Premier Prix, Maison Blanche Award, Photo Marseille - Winner2019 - Voies Off Awards, Arles - Finalist2019 - LensCulture Street Photography Awards - Finalist2019 - Kuala Lumpur International Photography Awards - Finalist2019 - Espy Photography Award - Finalist2015 - Prix Du Public Vile D’Hyeres Photographie

Publications PhMuseum - London BurningVostok Magazine - Climate Crisis IssueSuperstore WildernessPH Museum 2021 Top PicksSixty Six MagazineIcon MagazineCreative Review - Exposure, Gem FletcherGUP magazineMadame Figaro MagazineLes Recontres Philosophiques De MonacoAlvar MagazineLVMH MagazineExit MagazineArtsy Editorial

Exhibitions 2022 - Real Utopias - Collective Hub, Photo Fringe, Brighton, UK2022 - CTY / Unknown Places - Intervalle Gallery - Polly Tootal & Antony Cairns, Paris, France2022 - L'OEIL QUI VOYAGE - Intervalle Gallery, Collective exhibition, Paris, France2021 - LONDONS - The Polycentric City, Mass Collective - London, UK2020 - Mass Collective - Virtual Exhibition URBAN IDENTITIES2019 - Le Festival De Photographie de Marseille, Prix Maison Blanche - Marseille, France 2019 - Rencontres De La Photographie de Marrakech, Morocco2018 - One Contemporary - Venice, Italy2017 - Kestle Barton & Arts Council England - Cornwall, UK2017 - Unseen Photo Fair - Amsterdam, Netherlands2016 - Fotofever - Paris, France2016 - Unseen Photo Fair Amsterdam - Netherlands2016 - South Kiosk - London, UK2016 - Galerie Intervalle - Paris, France2015 - Unseen Photo Fair Amsterdam - Netherlands2015 - Hyeres Photography Festival Villa Noailes - France